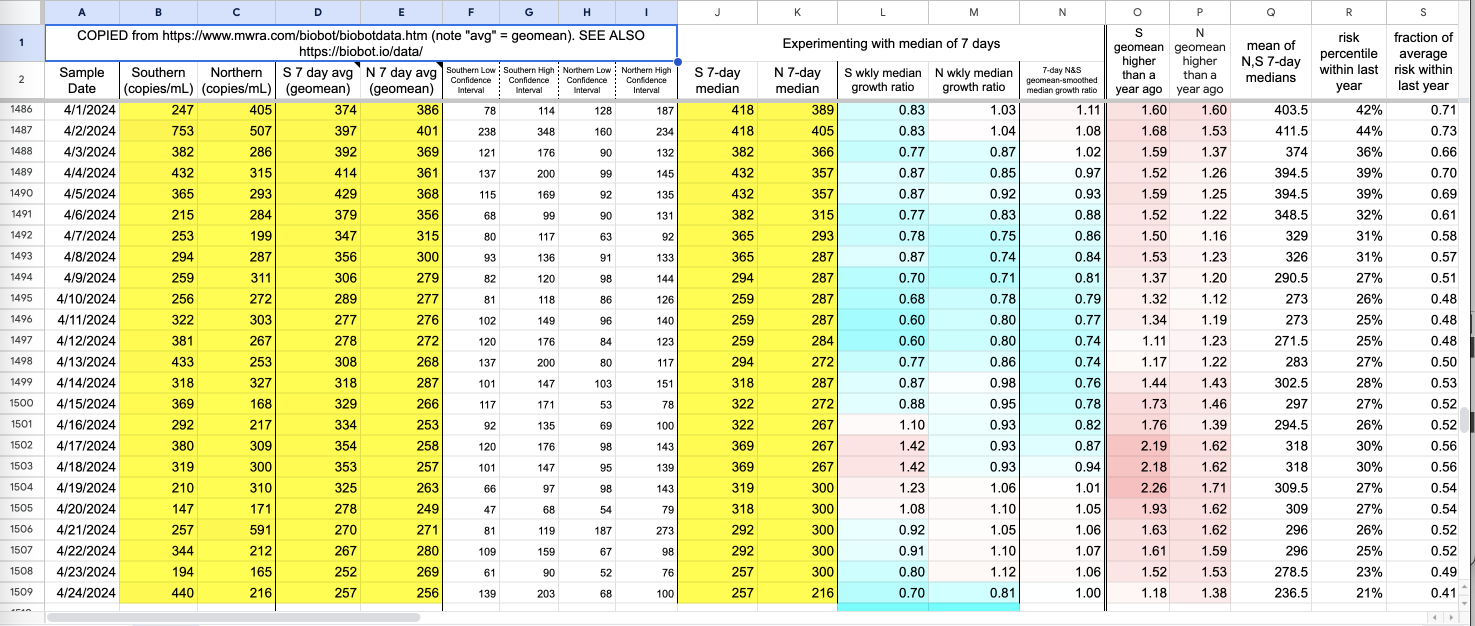

I’ve been copying the Covid RNA-in-sewage measurements from the MWRA’s website for a few years now, mostly so I could replot it on a log scale, but also to answer (vaguely, sort of, with caveats) questions about how we are doing. The short answer is we are not doing any better than we were last year, and have been behind more or less since mid-December.

As a guide, since it has grown columns over the years, the MWRA’s data appears in columns A through I. It is color-coded to show intensity, yellow is pretty common. The two columns that matter are D and E, which show the geometric mean of the last 7 days reported for the South and North sewer systems. 7 days includes each day of the week, so it avoids weekend/weekday effects. Geomean is used because it smooths out the noise in a process that grows exponentially

I experimentally also compute the median of the last 7 days, in columns J and K. This is another way of smoothing out noise. The weekly growth ratio, computed from the median, is in columns L and M, color coded with 1 is white, below one blue (blue is good!) and above one red (bad). I further smooth this in column N; the compounding of 7 day smoothing means this is a lagging indicator ( 7 days total).

In columns O and P, is the ratio of the MWRA’s computed geomean, with the same date a year ago, for South and North sewer systems. Same color coding, blue is good, red is bad. At least one of the two systems has been above one every day since mid-December 2023 (it is mid-April now).

It’s not certain that RNA counts are exactly comparable after a year’s time, given changes in the infected population and changes in the virus itself. Nonetheless, this is about the best data we’ve got, in terms of continuity and unbiased sample (everybody poops), and it says we’ve not made any progress. It seems odd that so many people are ready to act like we have; if they could point to some data to support their claims, that would be nice.

(Yes I have heard of one paper reporting that the virus strain du jour overexpresses in sewage. That’s one paper. One. How lucky do we feel, after a million-some dead?)

Florida and Climate Change

April 25, 2024

This is just a brief (I hope) gripe about the popular idea that Florida will be “underwater” in not too many decades. This is for the most part, wrong. I don’t live in Florida right now, but I grew up there, my father grew up there, my grandfather grew up there, and my great-grandfather stumbled into growing citrus there. I still have plenty of family there, and we visit often. It pains me to see people Wrong On The Internet.

If you look at predicted changes in sea level, most of them are still in the 1-2 meters by 2100 range. Florida and the East Coast will get some extra if the Gulf Stream shuts/slows down, but this is roughly a few feet more, probably not exceeding a meter.

So, worst likely case by 2100 is 10 feet of rise (and probably less). This will be a disaster, but lots of Florida will be well above water, because lots of Florida is well more than 10 feet above sea level. Unlikely cases involve surprising new things like a huge acceleration in ice cap movement, and those would be much worse.

So what sort of disaster is likely?

The Everglades are fucked — they’re very low, so a little bit of sea level rise will flood them with salt water. That’s a big change, it’s not clear what side effects it will have, either. But not too many people live in the Everglades.

Initially, long before a full 10 feet of sea level rise, we’ll have a financial and real estate disaster. A whole lot of people live on or near the water at relatively low elevation — all the populated barrier islands on the West Coast, for example. Just a little bit of sea level rise will make flooding far more frequent; anything not on stilts will become uninsurable, and even on stilts, people still have to descend to earth to get around. Roads and other infrastructure will get wet much more often, which will cause various sorts of damage. It’s “just inconvenience”, but more often, and if people are getting around by car (and the cars usually park under the stilt house) salt water flooding is unusually destructive, especially in a humid climate.

Local currents around the barrier islands will change with a different sea level, and that may cause the shore to retreat out from under structures. And in some low-lying inland cases, higher sea levels won’t flood directly, but the drainage will be that much worse, so flooding will be more frequent. All that flooded waterfront tends to have relatively well-off people living on it, so a lot of property value will be lost, and the rest of us will surely hear about their problems, and in some cases those noisy sad wealthy people will obtain political solutions (that the rest of us will subsidize).

And all this more-frequent flooding and less-rare destruction and expensive or unavailable insurance will have an effect on “property values”, which means less tax base for whatever town or city happens to include that property, at the same time that the municipality sees their own expenses rising. In the same way that property-owners find themselves unable to buy or afford insurance, municipalities will find themselves unable to borrow money at an affordable interest rate. Some of them will fail. Maybe some larger government will bail them out, again subsidized by the rest of us. This is not “government protecting people from a random disaster”, this is “government subsidizing unsustainable choices”.

The Gulf water temperature will be higher yet, which means even fewer freezes in the winter to knock back mosquitoes, and even warmer summer nights (every summer night the low temperature is the dew point — more humid = higher dew point = warmer nights). And, more violent storms; wetter air means more energy to toss around when that air is lofted to the stratosphere (that is what a thunderhead is), and warmer water means more energy to run hurricanes. I don’t know that it will get super hot (the huge bodies of water on both sides are very helpful at moderating extreme temperatures — for example, Tampa has never reached 100F) but it will be damn humid in the summer.

Fewer freezes means that mosquitoes will do better, and some of the tropical invasive species (pythons, nile monitor lizards) will thrive further north in the state. Mosquitoes are a big deal; Florida has historically had outbreaks of Yellow Fever, EEE, VEE, and SLE (E = Encephalitis) and dengue has popped up in recent years in the keys. More mosquitoes increases the odds of Zika or Malaria taking hold.

Higher sea levels will also mess with the water table; Florida’s geology is porous-mostly, and much of the rain that falls on land percolates down to the water table, and that accumulated fresh water pushes against all the sea water surrounding the state (this happens on a surprisingly small scale, I recall being shown a small source of fresh water on Caladesi State Park, a local barrier island). But higher seas will push back harder and move the drinkable water further inland. The porous geology also means that dikes are a non-option; the water will just flow underneath.

For central, vital infrastructure, like US highways, I expect that state and federal governments will mitigate for decades; they’re already well-built and well-drained, and raising just those roads won’t be that hard (there’s already plenty of bridges and causeways, we’ll build more, and higher). But, whole cities, some of them already flood in places at king tides, and that’s a lot to raise.

In centuries, especially on our present course, yes, the sea level will be many meters higher, and then indeed “Florida will be (mostly) underwater”. But centuries is a long time. (My great-grandfather moved to Florida about a century ago, and it has changed very, very much since then. I expect it will change some more as the oceans slowly but surely rise.)

Notes on Amsterdam

March 20, 2024

I’ve been in Amsterdam for a little over a week, spouse is in the middle of a long work trip and I am hanging out with her in her off time and otherwise I am touristing. I managed to put 40 miles on hotel guest bikes while here, 30 of that urban, 10, in North Amsterdam and north of that (which was lovely).

First nice thing to learn was that I bike well enough to (apparently) fit in. I have to get a little better about signaling to drivers in those places where I don’t need right-of-way; their default is to yield, which is very unAmerican. Lots of people here can and do ride no hands, I can and do ride no hands (it was easier on the first hotel’s bike). I got to experience a bit of weather; the first day it was cold and drizzly, the third, it was so windy that I might lose my stretchy hat.

Second interesting thing was that the infrastructure is not so much high quality, as high quantity and great-often/good-mostly. It’s not always super-wide, so everyone here seems to be good at riding in tight crowds. There’s trolley tracks all over the place, sometimes there’s turning bike path on top of turning trolley tracks and it seems like it would be easy to accidentally stick a wheel in that slot, and I did see someone catch a wheel and come close to crashing. There’s also plenty of bollards here to delineate boundaries, and some of them are right at the edge of the bike lane/path, and in other places there are large trees right at the edge of a lane and leaning into it (so that a tall person, e.g., one of the famously tall Dutch, might whack their head). Sometimes the surfaces are kinda bricky-y or cobbled.

I don’t really think that the urban routes (e.g., Ceintuurbaan) are uniformly “8-80”; some of that was parking protected, but some of that was not and there was a decent amount of traffic. In North Amsterdam, almost all of the routes we were on were clearly, obviously, friendly to all, but there was still one short segment where it was just shared road (but not a long stretch of shared road) that seemed a little iffy, to me, for very young riders. HOWEVER, in North Amsterdam, away from the small suboptimal bits, I saw (little) kids on bikes, just zipping around and doing stuff, again, very unAmerican.

The intersections tend to be very well designed with places for everything and separate lights for cars and for bikes and for each pedestrian crossing of each set of lanes (timed differently, not to strand pedestrians on a central island, but rather “this side can start walking 5 seconds earlier than that side”). Sharks teeth everywhere, pay attention, that will tell you who should yield. Lots of button-press sensors (separate ones) for bikes and for pedestrians and clearly road sensors for cars, as soon as the traffic stops flowing through an intersection, boom, their light goes red, someone else gets a green. It is a much more efficient use of space, that I had often noticed was used very inefficiently in the US (at many intersections timed lights will stay green long after traffic trails off, and realistically, the lights ought to turn as soon as traffic gets sparse if there is side traffic waiting). I think this cuts down on people on foot and on bikes crossing against their signal, both because they tend not to need to wait long, and also because if your signal is red it very likely indicates the presence of actual cross traffic. Nonetheless, I also observed plenty of people crossing against their signal when it was safe to do so, and twice noticed a car or motorcycle running a red (and also saw a taxi almost certainly speeding to make their light).

We had a car ride to a restaurant, well inside Amsterdam, driven by a Dutch civilian. We found parking not too far from the restaurant. Biking would have been faster. I would not want to drive; bicycle parking is far easier, and for a car things got extra complicated in a few places (for example, looking up a block to judge that it is too narrow with that trolley coming, so, just wait).

I liked Amsterdam, would visit again, would bike again. The unAmerican default is (for someone who is comfortable on a bike in bicycle traffic) that getting someplace on a bike is almost certainly a safe and easy option. I cannot help feeling that the US is full of people who have unintentionally disabled themselves by not riding bikes very much; things that are easy for me (and for the default Dutch), they just can’t do, for them it’s all walking or transit.

(And now I am in Paris, which has bike lanes, but lacks the default-it’s-all-fine-for-me feeling that Amsterdam has.)

Aging and measurement

March 17, 2024

I started utility biking seriously, and regularly, almost 18 years ago, and since then I’ve put about 46,000 miles on large, heavy cargo bikes. One useful thing about this is that I am regularly engaged in the same exercise, day after day, and even small changes can have noticeable effects, and over the years, I’ve also been able to sample different conditions.

So for example, when I changed from skinny tires to fat tires, that changed my commuting time, and I noticed. In one case, my first indication that I was coming down with the flu was “why am I so slow?” And over time, I’ve watched my commute times slowly increase, probably from age, maybe I had Covid once and it left me with a small but permanent cut in output, it’s not large enough to say for sure but I seem to be slower.

I’ve learned also, what my limiting factor usually is, which is O2 capacity. If I want to go faster, I have to “lead” with increased breathing, if I rely on oxygen demand to drive respiration, I will not enjoy the experience, at all. This knowledge was useful climbing steps at altitude in Yellowstone — “I need to breathe”, and so I do, and just let the legs work hard enough to use all the oxygen. I wonder sometimes if EPO would be fun.

Part way in to this biking adventure I started collecting video regularly, and somewhere along the way I realized that I could put an upper bound on my reaction time, by comparing the first possible moment when I might have noticed something, and when I began to react to it, and it is surprisingly good for an old fart — about 600 milliseconds, unchanged over the last eight years.

For Covid, we got one of the little fingertip O2 meters, one experiment I tried was to ride my bike with one on my finger, and it was really cool, I could finally see what “warm up” was all about. At least at that age, when I first start biking, my body does not take the effort seriously, does not ramp up the metabolism, and as I (try to) expend energy, my O2 levels drop, my heart rate spikes, and not much happens. After a while, the body quits these lazy shenanigans, everything revs up (if it is in the winter, this is right about when I notice that I am warm, DUH, I wonder if that is a clue?) the O2 pops back to nominal or even a little above, the heart settles down to a steady rate, and away I go.

I ordered a fitbit earlier this week, I am a little curious to see what I find out. I’m not sure what my resting heart rate actually is, I am usually doing stuff, sitting still is boring. When I was 58, getting an EKG at the doctor (enforced horizontal sloth), she remarked, “your age is your heart rate, not bad” but I was already well-dosed with coffee.

A few weeks went by since I wrote the previous, and the RHR seems to correlate pretty well with stress. Fitbit measures it to be 60-61 most of the time, when getting ready for a trip to Europe and immediately afterwards, 63-65. Settled down with spouse, touristing around and not worrying about stuff (also got recent random good news from two younger kids, so, yay), finally getting some solid nights of sleep after working through jet lag, and it declines to 60-61, then 58 (which is low, but might be my unstressed baseline).

Real estate developers

January 15, 2024

I am on Team Yimby because housing supply has not met demand for years, that causes prices to spike, and makes life hard for very many people younger and/or less lucky than me. However, building more houses means someone needs to build them, and that ends up being real estate developers. My experience with them over the years has usually been non-positive — perhaps because I grew up in Florida.

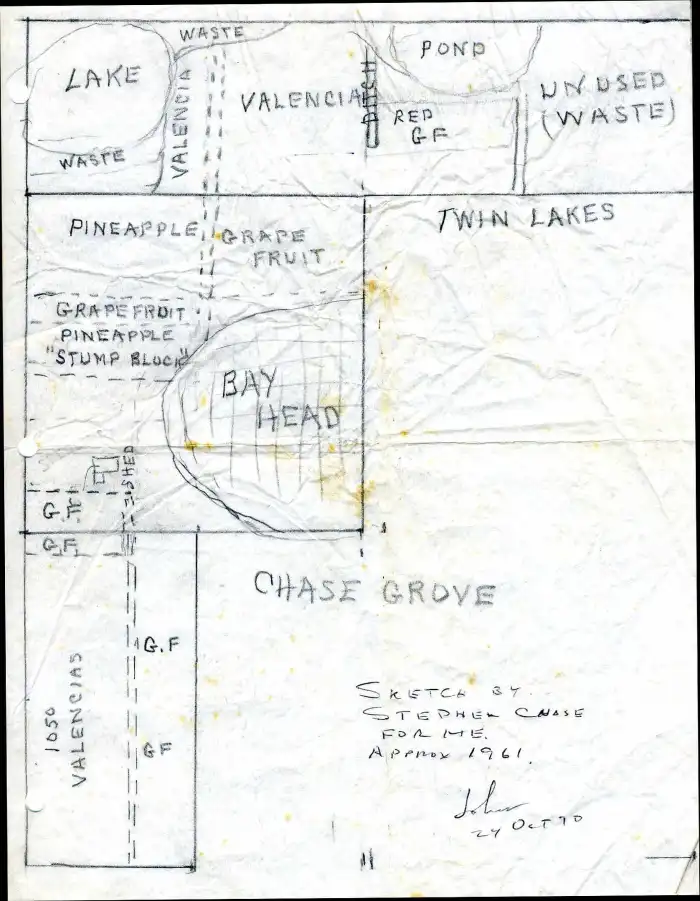

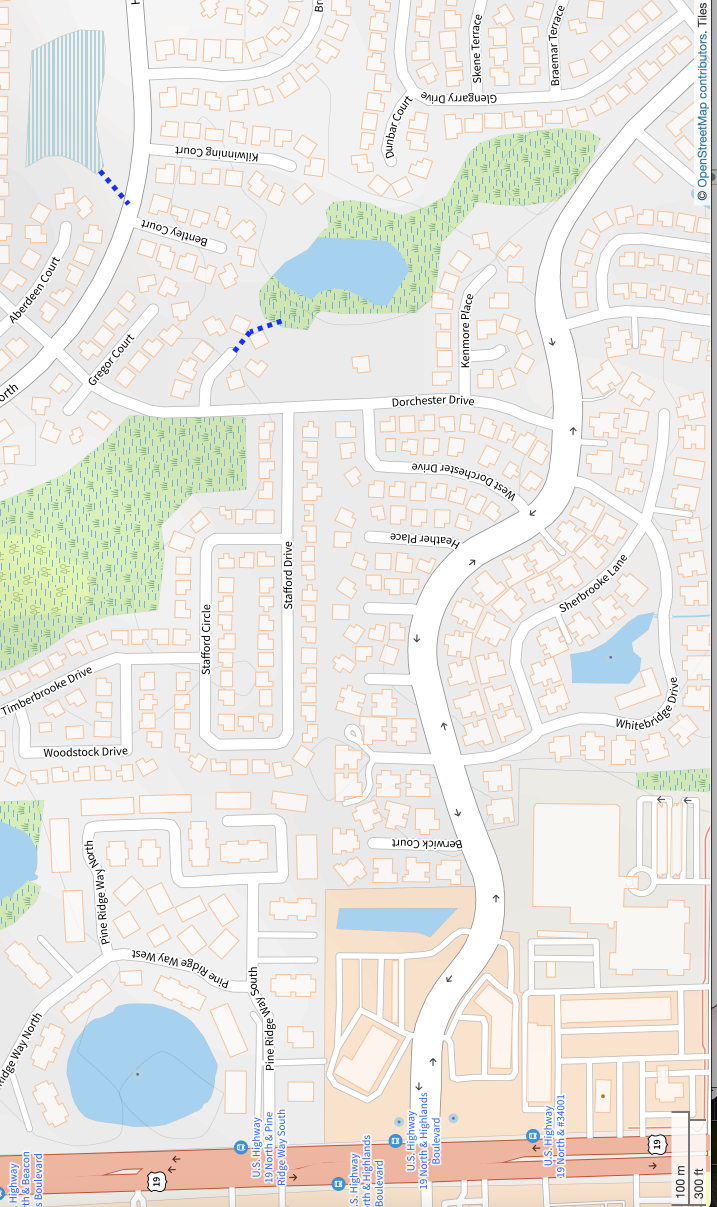

I grew up in Florida, in an orange grove, about 1/2 a mile from the nearest paved road. Nearest neighbors as the crow flies were either the Stantons or the Eagles. Everything around us was mostly citrus, swamp, or sinkhole (swamp is a special case of sinkhole, an old one that collected water, grew stuff, which eventually fell into the middle and made peat. “Bay head”, below, is swamp). My great grandfather once owned a chunk of it, and gave my parents land to build a house on.

Greatgrandfather sold to someone, someone held it a few years and sold to U.S. Homes, who proceeded to build “Highland Lakes”.

U.S. Homes was as far as I know about middling, for land developers. I never heard of any particular scandals, for example. However, from the point-of-view of someone who knew the local territory pretty well (as well as one can know it by age 12) they were not the brightest bulbs. For example, we lived half a mile from a paved road. I wonder how we got to that paved road, eh? Could it be, on a 1/2 mile by 8-feet 99-year easement across the north edge of the property? Why yes, it could. Easements survive sale of property, just FYI, so pretty soon, we were walking through newly-purchased backyards to get to the school bus (not kidding, didn’t happen “sometimes”, we did this, every day, it was the shortest route and the one we had been using since an early age).

I gather that this caused problems, and this was eventually solved by trading the easement for a $15,000 bond set against future legal costs should we need to sue them for incidental damage to our property. (Keep in mind, early 1970s, that was real money.)

Another mistake they made was to misread topographic maps. Somehow, they convinced themselves that the water in our pond had collected at a high point, not a low point, and that water drained out of our pond. Any fucking fool who just walked out and looked could have seen that was not how things were arranged. Somewhere in all this land rearrangement they monkeyed with the drainage, and the pond started going up, and up, and up, enough that it was killing trees and we could imagine it causing problems for our septic system’s drain field. We grumbled at them and made threatening noises about that bond, and they installed an overflow, like for a bathtub, for that pond. My best guess as to the least-cost route for that overflow is shown in dashed blue, below. The overflow drain is a large sinkhole with a porous bottom; water will accumulate there, but eventually disappears. You can tell which drain pipe into it comes from our pond; there’s far more weeds/wildlife there.

In their zeal to market the height of Highland Lakes, it was not enough for them to be high, one must also perceive them to be high. To help with this, US Homes sculpted the main road down below the houses that they built, I think also using some of this earth to raise the land around the bayhead.

One problem with this is that the water table in Florida is very high, is also quite variable, and sometimes it can be quite rainy. One day walking to school (no longer on the 1/2 mile easement) I noticed that the road was not really a road anymore, and was instead a mixture of gooey wet roadbed and asphalt crumble; the water table had risen under the road, and then a construction truck was driven on that, and the roadbed was now fluid and just squirted up through the asphalt and blew it apart. Naturally, they repaved the road without addressing the root cause, it rained again, someone drove a truck again, and it happened again. THIS TIME, before repaving, they installed a drain field, more or less a french drain, running along the edge of the road, to redirect the water table away from the sculpted road.

So, anyway, developers are bozos, but I am still on Team Yimby.

I write letters (to my state rep and senator)

November 19, 2023

Thought I would harass y’all (again) about stuff I care about, I’ll try to make it short and not show too much of my work. (This would be shorter if we didn’t have so much broken stuff that needs fixing.)

Infrastructure dithering

October 20, 2023

One thing that completely baffles me about some of the delay in doing things — for example, in building wheel-chair accessible ramps at train stations, or experimenting with different ramps and elevations for complex portions of bicycle lanes — is that for some reason we insist on making them only from incredibly permanent materials, thus their design and construction is expensive, thus we delay, delay, delay with planning and interminable community discussion, lest we carve the wrong thing into stone and steel. We could, instead, work in marine plywood, which with minimal care appears to last at least 15 years outdoors exposed to the elements (I have a deck on my bicycle made of marine plywood that is that old; the original came apart in just a few years).

And yes, marine plywood is expensive plywood, but it doesn’t require fancy tools. Could pre-cut most of the parts off site, deliver, and assemble. Or if it is a complex design in a quirky place, it doesn’t take that long to do a custom job on-site, work in the off-hours. Use treated lumber where appropriate, soak the cut ends in marine anti-fouling paint to keep the bugs out. That gets us a low-cost prototype that lasts for a few years, if it works, we redo it in concrete, if it doesn’t, we try something else.

A second annoying thing is what I can only call inappropriate use/requirement of rules and standards. In Cambridge, at the larger Fresh Pond rotary, there is a big sign informing east-bound traffic of what happens at the intersection. The design and location of the sign are completely bullshit; it’s obviously built to help ensure safety of traffic moving twice as fast as anything on that road, but because it is thus-and-such a highway, I’ll bet those are the rules. So, it is located a safe distance from the road (but right next to a cycle track) which allows the trees near the road to obscure it from the traffic that needs to see it. And, rather than a plain post, it is on a special breakaway post, just in case someone departs the road at twice the speed limit, plows through numerous other obstacles, and manages to not hit any trees — that sign, it will break away, and protect them.

How I ended up on team YIMBY

October 15, 2023

A few observations changed my mind from “pro housing but we need deal with these problems” to “pro housing”.

The first observation is that in the face of high housing demand, our zoning laws are completely indifferent to the demographics of who can afford to move into a region, and only speak to the shape, size, and placement of the boxes that we live in. Is a town, and a town’s “character”, the boxes that people live in, or the people who live in those boxes? If the middle class can no longer afford to buy in a city or town, over time that city will lose its middle class, and its character will absolutely change. But the boxes, those at least are preserved.

The second observation is that the problems associated with greater housing density are problems that we can deal with local-ish. The two main problems are school funding and traffic; in both cases these have state and local/regional solutions, and we can elect people who favor solving these problems. Traffic is a squishier problem but we also have a lot of tools that we can use to mitigate it. We need to get our transit fixed; it worked decently well thirty years ago, why not make it work well again? We can also run it even better, if we are willing to pay for it. We could extend it further out, if we are willing to pay for it. We can run better rail to suburbs and chip away at some of that traffic. We can improve cycling in the cities and towns surrounding Boston, Cambridge, and Somerville; for plenty of people, their commutes (and their errands, actually more trips than commutes) are possible on a bike. (If you don’t know how to deal with groceries, kid transportation, or winter, other people do, it’s not hard, it just requires the right bike and a little knowledge.) We could pass a congestion tax, IF we do it before housing prices get too high — someone willing to pay $2million for a condo will not be substantially deterred by small fees for driving into crowded places.

The highest demand for more housing is closer to jobs, which are largely in Cambridge, Somerville, and Boston, so if new housing is created where demand is highest, it will generally have a higher chance of not needing a daily car trip.

Edit/addition, 2023-11-25: For many towns, “traffic” is also not caused by local density, but by people traveling through a town. If those people are in cars, one thing they do, is always seek the currently fastest route, nowadays updated with same-hour congestion reports. This means that any locally-influenced traffic changes (increase or decrease) will be counteracted by cut-through traffic adjusting to that change. The local “solution” to this problem is to decouple local transportation from automobile traffic as much as possible; allow businesses close enough to where people live that they can walk, provide safe and comfortable bike routes so people can bike, and reserve lanes for bus use so that traffic increases don’t affect bus speeds. And, try to reduce cut-through traffic with long-haul alternatives, like better rail to suburbs.

The third observation is that the problems that result if we don’t build enough new housing to meet demand w/o substantial price increases, are problems that we cannot easily solve. The higher prices are allowed to rise and the longer the high prices persist, the greater the effect on the town’s demographics. That change is roughly permanent. Adding supply at that point will perhaps, instead of stabilizing prices, depress them, leading to recent purchasers underwater on their mortgages; it’s a lot of real economic harm to them. And at least the initial tranche of any new supply will be at the high market, and will continue (through addition rather than replacement) some of the same demographic changes resulting from the spiked-high prices.

High unit prices also make it more difficult to construct legally-defined-affordable housing; any unit sold at an affordable-instead-of-market price means that someone, somewhere, is subsidizing that difference, and the larger the difference, the larger the subsidy. One way out of this is to permit higher-than-usual density if some units are affordable, but that still throttles supply, and still leaves no housing supply for the middle (given high enough prices, upper-middle) class.

We’re terrible at road safety in the United States

October 14, 2023

This is one of those things that I never noticed till I did, and now I can’t not know it, and makes me internally snark at anyone in conventional US road safety institutions discussing/promoting “road safety”.

There’s three reasons to think we suck at safety.

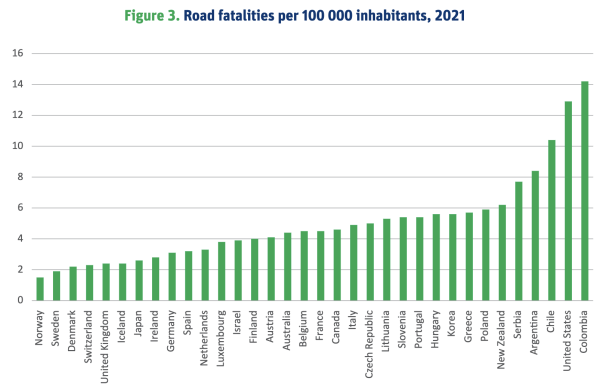

First, international comparisons by the OECD.

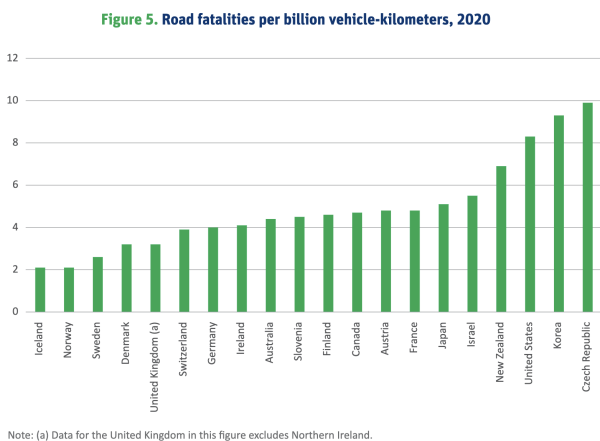

“But wait”, you say, “we’re a big country. Surely this is because we drive so much.”

And yes, congratulations for realizing that excess driving is its own risk amplifier, but actually, we suck at driving per-mile (or kilometer) also. Maybe if we didn’t suck at safety we’d try to reduce distances driven until we got our risk-per-mile under control, but we suck at safety:

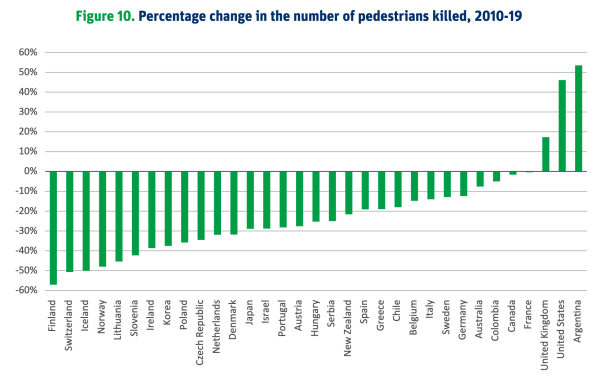

Second, recent history, where we slid backwards pretty horribly.

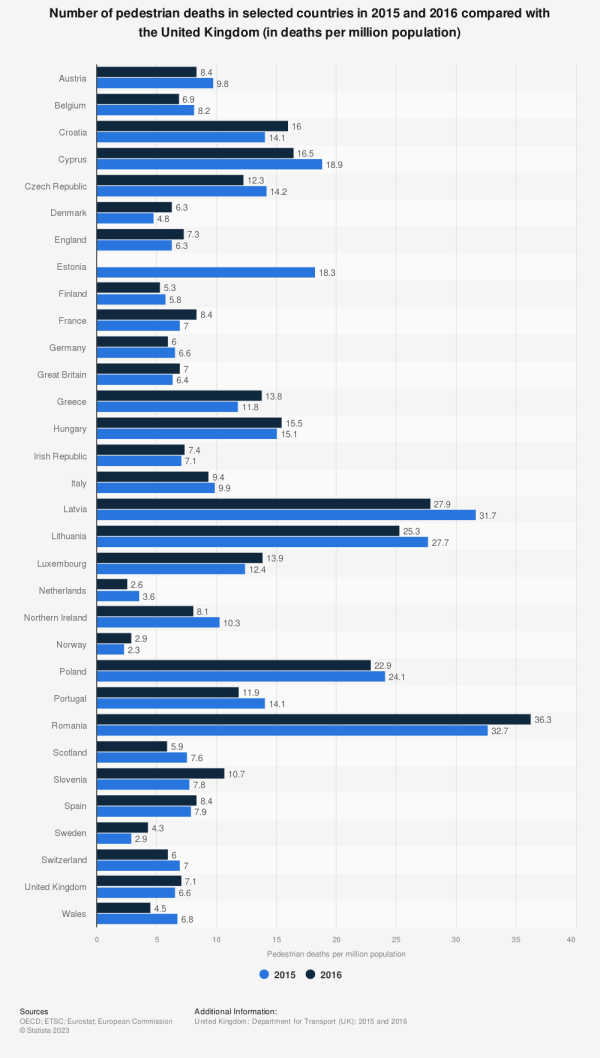

Third, the popular attitude towards bicycles and pedestrians in any US safety discussion. For a little context, another chart from the OECD:

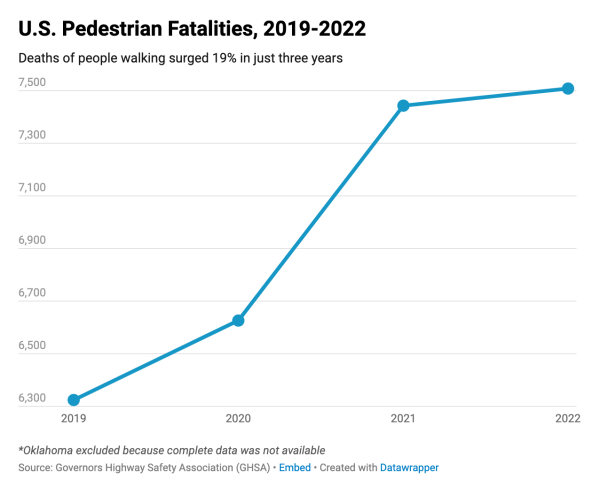

We’ve only done worse since then:

Or, if you prefer a per-capita comparison, for the US in 2022, 22.8 pedestrian fatalities per million population, worse than all the nations here except for Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania. For Massachusetts the rate was 14.3, New York 15.1, Texas 27.8, California 28.2, and Florida 37.0. Our “good” states are still about twice as deadly per-capita as countries we’d like to think of us our peers, never mind the “good” Scandinavian countries where the pedestrian crash death risk is only about 1/4 what it is here.

The usual US reaction to this seems to blaming “distracted pedestrians”, as if we were the only nation on earth with hand-held distractions.

Anytime anything bicycle-and-safety-related comes up, some chirpy ignoramus will helpful contribute “but bicycles are dangerous to pedestrians!!!”. In the US, crashes between bicycles and pedestrians kill about 1 pedestrian per year, usually someone in New York City, the only place in this country with both enough bicycles and enough pedestrians to make this event roughly likely. Not adjusting for trip share, the car-crash pedestrian death rate is SEVEN THOUSAND times higher. Dividing that down by the bicycle trip share makes the risk a mere 40-ish times higher, but in most safety discussions 40x is a darn large factor. Once again, we (in this case, drivers, by far the majority road user) are bad at safety and seem not to even be aware of it.

And, okay, snarky blogger guy, what would YOU do about safety? One problem we have is that we drive a whole darn lot while our per-mile safety is poor. I would stop building roads; driving less is one way to drive more safely. Our stats wouldn’t suck so much if we drove less. Another thing I would do is impose lower speed limits any place pedestrians are near the road. And by lower, I mean, 15mph. Rather than rely on enforcement, I would install hard bollards along the edges of the road that I wanted to have this lower speed limit, so as to encourage a little more care. Bicycles tend to go about that slow, and bicycles have a much better safety record, let’s try this. A third thing I suggest (and I do) is I do not use a car when I can get the job done on a bicycle. The car that isn’t driven is safe; using a bicycle instead is a 97-98% risk reduction, that’s pretty good.

Safety training, habits, and reflexes

October 1, 2023

For a while I’ve believed that too much of popular (and sometimes legal) approaches to road safety are built around fairy tales. For example, the idea that horns are a safety signaling device for anything other than “that guy is backing into the front of my car” is just a fairy tale. In forward motion, which is usual case for crashes, brakes are far more effective than a horn because they only depend on one person perceiving and reacting — you, the person who sees the problem first. Braking reaction time could be better, if, say, a car used hand brakes like motorcycles and very many bicycles, because that way it’s not necessary to move a foot from one pedal to the other, but one person’s reaction time is still shorter than the sum of two people’s reaction times. The horn is also broadcast, and low-bandwidth, so really the second person’s reaction is to look around to consciously figure out what is wrong, and then react to it (and that assumes they will react appropriately and productively, of course).

For bicycles, our road safety wizards decided to copy this fairy tale, substituting bells for horns. There are better ways to do bicycle safety than copying ideas from cars, never mind copying dumb ideas from cars.

A second dumb thing that we do for car safety is that we create two categories of pedestrians crossing the street, “legal” and “jaywalkers” and then we obsess over the distinction between the good ones and the bad ones. This, too, bleeds over into bicycle safety, and it is counterproductive. We are not junior police, it’s not our job to shame the illegal walkers, it’s our job not to hit them.

You might think, “so what if I worry about these things? I still stop, don’t I?”

But I don’t think you stop as well. Thinking about whether we should stop, or stop and ding, or just ding — that takes time, and if that is our habit, it will always take time. It’s better to train yourself to always stop/swerve first, ask questions later. Make the faster process into a habit, and eventually, you will train your subconscious to do it automatically.

I’ve recorded video of most of my commutes over the years, saving the interesting bits, and some of the interesting bits are how I react to pedestrians that I see around me, and how quickly. Recently, I reacted to a pedestrian turning to cross a street before I consciously knew it; someone had placed a utility box in such a way that it obstructed my view of the crosswalk entrance, and when I tried to reconstruct the reaction in the way that I remembered (my conscious experience, for better or worse) I got a completely impossible reaction time of not more than 300ms. I looked at the larger video again at 1/10 speed, and it became clear that some part of my brain had seen her starting to turn, figured out what was happening, and even earlier than I first thought, initiated a letter-perfect snap turn; I was already committed to the turn before I saw the pedestrian emerge on the other side of the box. This was a trained, complex, automated reaction, and I can do this now because I have made a habit of always swerving away from pedestrians and not complicating my reaction with a bunch of decisions that are not actually relevant to safety.